LPRC participates on a new EIT RawMaterials Education project!

TIMREX is a newly started EIT RawMaterials project that will…

ROBOMINERS

ROBOMINERSROBOMINERS Consortium Meeting with LPRC in Austria

The ROBOMINERS Consortium, in which LPRC participates, hosted…

INCORE

INCORELPRC was in the Madeira Island for the first in person INCORE meeting

After a few months of online collaboration, the INCORE consortium…

LPRC participation at CROWDTHERMAL meetings in the Netherlands

Between the 6th and 8th of October 2021 the CROWDTHERMAL consortium…

INTERMIN project Final Review Meeting

The INTERMIN project held its Final Review Meeting with the EC…

LPRC active during the last MOBI-US project Workshop

The final event of the MOBI-US project was held in Zagreb, Croatia,…

The MacaroNight 2021 is today – do not miss it!

Our MacaroNight project, part of the European Researchers' Night,…

The MacaroNight 2021 is fast approaching

It is already this Friday, 24 September 2021, that the European…

INCORE 2nd project meeting

Following the first official Kick-off meeting, the INCORE team…

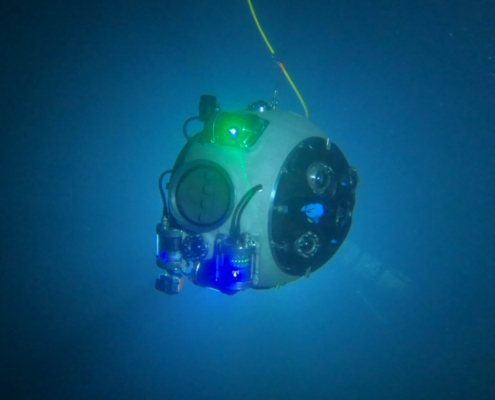

UNEXMIN GeoRobotics

UNEXMIN GeoRoboticsLPRC representing UNEXUP at RawMat2021!

From 5 – 9 September 2021 the academic community, engineers,…